Bedouins of Egypt

4.8 / 5 209 ReviewsBedouins of Egypt

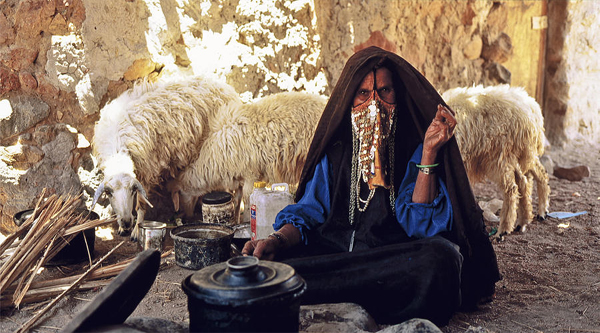

Traditions, culture and way of life of the Bedouins of South Sinai, Egypt

Where Bedouins live

Bedouins have traditionally occupied the Sinai Peninsula . Within the limits of declared Protected Areas they retain their traditional rights and continue to occupy their settlements, women graze their sheep and goat herds and men fish. Enduring the desert and walking through rough mountains is part of Bedouin women's life.

The tribal law

Bedouin culture has been founded on strict tribal laws and traditions. Tribal law prohibits the cutting of "green trees", the penalty could be up to three 2 year old camels or their equivalent value. Bedouins have said that "killing a tree is like killing a soul”. Bedouins are desperate for water, sometimes having no rain for up to five years.

Bedouin Population in Sinai

Bedouin populations in Southern Sinai (descendants of tribesmen who settled here some 800 years ago) are broken down into 8 tribes. About 7,000 people live around St Catherine's. While the largest number belong to the Jabaliya tribe, others are from the Muzeina, Gharaja, Sawalha, Aligheit, Awlad Said and Beni Hassan. All are Arabs -- that is, coming originally from the Saudi Peninsula -- apart from the Jabaliya, who were brought to Sinai from the vicinity of Macedonia in the sixth century to provide security and service to the monks at the new monastery.

Nabq and Abu Galum protectorates

The Managed Resource Protected Areas of Nabq and Abu Galum are inhabited by two of these tribes, the EI Mezeina - one of the largest and most powerful tribes - inhabits the Southern Gulf from Nuweiba to Sharm el Sheikh. Nabq protectorate administration is Bedouins who have been settled there for decades. Of the eight Bedouin tribes of South Sinai , Al-Muzeina has by far the greatest share of Nabq and that tribes people have a set lifestyle. Bedouins are used to limitations and they are inherently environmentally aware. For them cutting a tree was a major crime that solicited a trial in which the culprit would be severely punished. They have been here for decades and if they did not protect our environment, would we have found all those resources? Nabq Bedouin are grateful because if it was not for the protectorate they would have been displaced.

El Tarabin tribe

Another tribe - the EI Tarabin occupies the area from Nuweiba to Taba. So that the local bazaars overflow with Bedouin products, such as handmade silver and bead jewellery, and brightly coloured woven throws and wall-hangings. The total Bedouin population in these areas is approximately 3000 individuals.

The Jebeliya (the tribe of the mountain

The Jebeliya (the tribe of the mountain) – probably only about 1,500 people they have a very small tribal territory around Mt. Sinai, this tribe occupies area of Saint Catherine and guard the monastery for centuries. They believed that they are the descendants of the roman solders brought to Sinai by emperor Justinian to guard the Monastery of Saint Catherine. The Jebeliya tribe is not descendent of Arab origin, but rather of, oddly enough, eastern European. It is believed that the Roman Emperor Justinian I, who ordered the building of St Catherine Monastery during the sixth century, had sent a hundred or so guards to protect and serve the monastery. They later intermarried with the locals and formed a separate tribe. Over the generations the Jabaliya married members of other tribes and gradually converted from Christianity to Islam, but continued to work at St Catherine's Monastery. The Jebeliya maintained a symbiotic relationship with the monastery's monks.

Other tribes

Awarma, Awlad Said & Qararsha (Suwalha): also live in South Sinai and represent one of the clans of overall Suwalha tribe.

Crafts

To encourage Bedouin crafts in southern Sinai a Bedouin Support Programme has been started. The flora and fauna of the region is reflected in the embroidery of the women and their work is marketed at the Saint Catherine Protectorate Visitor's Centre but in the beginning Bedouins were a bit hesitant on hearing about Saint Catherine being a protected area.

When the Bedouin Crafts of South Sinai started, women became so happy and enthusiastic. They were happy to do something that could bring their families a bit of money, apart from their responsibilities including home management, shepherding and raising children.

Women dresses

The Bedouins of Sinai and the Eastern and Western deserts have their distinctive clothing. Black is the predominant Bedouin dress colour for women. The Bedouin women's characteristic garments are richly embellished with fine hand embroidery -- mostly in red, pink, orange, yellow and turquoise -- worked in cross stitch. The intricate dress designs are artistically embroidered across the front and back of the bodice. Married women wrap a black cloth known as asaba around their forehead.

Dress is a sign of a social standing

A Bedouin woman's dress is a sign of her social standing, her hairstyle of her age or marital status. Every unmarried Bedouin girl, for instance, sports a lock across her forehead, but this is substituted by a plait in an elderly woman. Married women of the Jabaliya tribe wear a black shawl ( Al-ghurna ), unmarried girls a white one , ( Al-malfah ). A married woman wears a long face veil ( Al-burgah ), a bride a short one until she has had her first child. In North Sinai women wear an open veil, a beaded breastplate ( Al-mallab ), and metal accessories given by her husband in the first months of her married life.

Dress styles

Styles of dress women wear at different stages of their life are varying from bright colours to a dark one. When seven years old, a child wears a printed colourful dress and no head covering. Then at 12, she begins to wear a second dress, black and sleeveless, on top of the first. In the past, a girl of 12 wore a athma, a small face covering without decoration, now they wear a tarha which can be worn in different ways to cover the head and mouth, usually decorated at the edge with brightly coloured beads.

Women hairdressing

At the age of 14 or 15, Bedouin girls adopt the gebla hairstyle, two plaits crossing the forehead. In the past, a girl showed she was ready for marriage by fashioning her hair into a gossa, which is a plait made into a bun on the forehead, which she maintained after marriage. At this stage, she usually added the shebeka or ghodfa, a small head covering with small pieces of shells attached. After marriage, the girl dresses her hair in a new style, masaih, which is an elaborate interlocking style dividing the hair into two parts covering the forehead,"

Dress of a Bedouin man

Galabiya, a long, hooded robe and 'oqal (headrope) is a typical dress for Bedouin men. The most easily recognized aspect of a Bedouin's attire is his headgear which consists of kufiyya -cloth and 'agal -rope that constitute proper attire for a Bedouin man. The head rope in particular carries great significance, as it is indicative of the wearer's ability to uphold the obligations and responsibilities of manhood.

Bedouin department of the Visitor's Center in St. Catherine

In the Bedouin department of the Visitor's Centre in St. Catherine you can find on display wedding shawls (the gon'a or herga) incorporating sequins and coloured beads in the design and edged with brightly coloured pompoms, bags carried by women attending flocks of goats and sheep and kilim rugs used both domestically or to drape over the backs of camels. Among the most attractive pieces on display are sugar bags, which contain a pocket for tea, an essential part of the baggage Bedouin men carry on longer trips, emblazoned with brightly coloured foliage, flowers and animals.

Traditions of the Bedouins

Many of Sinai's Bedouins continue to harbour a deeply traditional allegiance to the tribe -- in effect an extended family -- above all else. They always think of the whole tribe as their family, and they always try and help each other. Most of their time is spent on that. In most cases Bedouin women will cook for a significant part of the day as guests will walk in and out all the time and it's only natural for them to be able to eat.

Bedouin tent

A bedouin tent is customarily divided into two sections by a woven curtain known as a ma'nad . One section, reserved for the men and for the reception of most guests, is called the mag'ad , or 'sitting place.' The other, in which the women cook and receive female guests, is called the maharama, or 'place of the women

Women in Bedouin society have very strong position. They are equal to men, each has her own job, and the women keep their own money.

Bedouins have to respect the tribe and the traditions of Bedouin marriage as well. Old Bedouin tradition of marriage proposal represents the boulder with foot-shaped engravings in mountains. The man went to the rock and engraved the outline of his foot after which the girl would add hers beside it. If the father agreed to the marriage, a circle was drown around the two footprints. Not every proposal had a happy outcome. Unfortunately this old Bedouin form of marriage proposal no longer practiced.

Ownership in the desert among Bedouins isn't decided according to written contracts, but rests instead on verbal agreements. If you grow up near a Mountain you will take the site as your home. The Palm Tree as a rule marks the boundaries of different tribes, along with springs and can indicate a Bedouin's land. "My grandfather planted this tree here, therefore this is my land," is a common remark from the Bedouin when disputing land writes, even when a piece of land has not been inhabited for some time.

Palm trees

Palm Trees are now their main agriculture for Bedouins of South Sinai, they sell the crop while still hanging on the tree or they collect the seeds and store in goat skin bags, which are cleaned with the Mardagosh herb. Sinai Bedouin believe herbs to be healthy and therapeutic, that's why they are used as a part of their daily diet, brewed up on open fire.

The Bedouin are natural conservationists

The Bedouin themselves are natural conservationists, it's part of their heritage, they have a system of alliance through which they protect wild plants and animals. They will close a certain valley for three to six months to prevent grazing until it has regrown, to respect sustainability.

Bedouins and their graves

Bedouins mark their graves with exceptional simplicity, placing one ordinary stone at the head of the grave and one at its foot. Moreover, it is traditional to leave the clothes of the deceased atop the grave, to be adopted by whatever needy travelers may pass by.

Poetry

The Bedouin have developed their own way of passing information down through countless generations in a colourful, animated and musical form of poetry. This they recount at 'EI Magaad', a meeting of the men folk, in which the unwritten laws, politics and economy of the tribes are told in their classical Arabic language. By adding rhythm and rhyme to the stories they're less likely to become distorted over time.

The first, most testing, form of delivery is the Daheya, which is performed by the more expert elderly poets. The tribesmen form a line as the elder recounts his tales of wisdom, with the men chorusing one word from each verse.

The second form is known as Marboa. Where the rhyme is accompanied by a rhythmic drumbeat and the women of the tribe dance in front of a single line of men with their veils held out wide, a little like a Red Indian eagle dance, chanting and warbling with their tongues.

The third and most party like form is the Rafehi where two lines of men face each other whilst the women dance between them. One of the lines start by chanting the first verse and the second line 'answers' them and so the exchange continues.

Traditional instruments

The traditional instruments of Bedouin musicians are the shabbaba , a length of metal pipe fashioned into a sort of flute, the rababa , a versatile, one-string violin, and of course the voice. The primary singers among the Bedouin are the women, who sit in rows facing each other to engage in a sort of sung dialogue, composed of verses and exchanges that commemorate and comment upon special events and occasions.

Food of Bedouins

Bedouins are famous for their hospitality and warmth. They wait on you as if you're a king. Before you have time to ask them for something, they're already doing it for you.

It is said in Islam that god gave humanity the Palm Tree for sustenance. It was a source of life for the Bedouin, their traditional staple diet included dates, milk of goats and camels, baked bread and the fat of the goats.

I bet you have eaten rice, potatoes, and chicken a million times before, but you haven't eaten them in the Bedouin style. Coal is the key. Chicken and kofta are grilled directly on the coal, while the rice and potatoes are cooked over the coal fire too.

Bedouin bread

Bedouin bread is a whole other story. Freshly baked, served from the oven to your plate, it melts in your mouth and it tastes like heaven. That's why Bedouin bread is not to be missed. Libbah is the king of Bedouin bread, made of dark wheat, water and salt. The paste is rolled flat and buried in the sand with hot coals placed on top. It is turned over once, then tapped on to test when it is ready; well baked, not a grain of sand sticks to it. Another kind of bread, farrasheeh, also made of dark wheat but this time thinly spread over a concave piece of metal and baked directly in the fire. The result is a large thin bread with holes. The taste almost beats that of libbah.

Food of reach Bedouins

Some rich Bedouin can afford dishes such as mandy , which is goat meat buried in sand to be heated slowly by the rays of the sun. A few days later, the goat is taken out, rapped in tin foil and cooked on coal.

Bedouin tea

Bedouin tea tastes a lot better. Added to tea is habak , a mint-like herb that grows in the Sinai desert in winter. Mashed with tea and boiled on coal, the result is unique and delicious.

Modern Bedouins

The Bedouin have changed over the last century, and how the term Bedouin has evolved from a lifestyle to being an identity. Although the word Bedouin still evokes a tent-dwelling community forgotten by time in an inhospitable stretch of desert the reality is often quite different.